Table of Contents

In an era where modern agriculture is heavily reliant on synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, and high-input farming techniques, Masanobu Fukuoka’s The One-Straw Revolution offers a radical alternative to conventional farming practices. Written by the Japanese farmer and philosopher, this groundbreaking book challenges the very foundation of industrial agriculture, advocating for a return to nature through minimal intervention. Fukuoka’s philosophy of “natural farming” encourages a more harmonious relationship with the land, where the emphasis is on working with, rather than against, nature’s processes.

Fukuoka’s ideas, which span from no-tillage practices to a rejection of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, provide a powerful critique of the dominant agricultural paradigm. At its core, Fukuoka’s philosophy is about rediscovering humanity’s place within the natural world. His ideas encourage us to see farming as more than food production—it is a way to cultivate healthier ecosystems, stronger communities, and more meaningful lives. This article explores the profound insights of The One-Straw Revolution, examining its practical applications, critiques of modern agriculture, and enduring legacy.

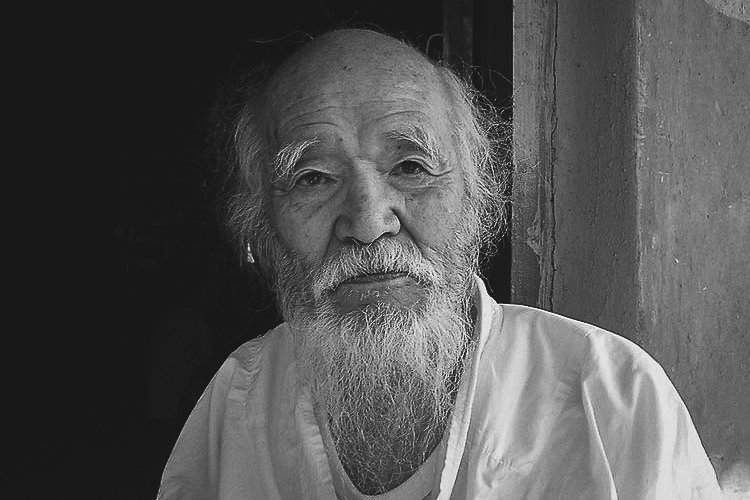

Who Was Masanobu Fukuoka?

Masanobu Fukuoka was a revolutionary figure in the field of agriculture, yet his journey was unconventional and deeply personal. Born in 1913 in Ehime Prefecture, Japan, he initially followed a traditional academic path, studying microbiology and specializing in plant pathology at Kyoto University. His work as a researcher focused on diseases affecting citrus trees, a major agricultural concern in his region.

However, despite his scientific successes, Fukuoka became disillusioned with the limitations of intellectual understanding. A turning point came when he contracted pneumonia, which left him bedridden for a time. The physical recovery was followed by a profound period of existential questioning and depression. It was during a solitary walk in the hills near Yokohama that Fukuoka experienced a spiritual epiphany. Watching a night heron in flight, he felt an overwhelming sense of connection with the natural world and realized the futility of trying to dominate or outsmart nature through intellectual means.

This realization led him to reject the scientific rationalism that had guided his career. In his own words, he discovered that “it is impossible to know anything truly through intellectual efforts.” He believed that the mysteries of nature could only be understood by living in harmony with it.

Determined to put his newfound understanding into practice, Fukuoka resigned from his research position and returned to his family’s citrus farm in Shikoku. There, he devoted his life to developing and refining a method of “natural farming.” This approach was based on simplicity, rejecting artificial inputs, and allowing nature to take the lead.

Fukuoka’s decision to abandon a promising scientific career for a life of manual labor shocked his contemporaries. Yet, his unwavering commitment to his principles transformed him into a pioneer of sustainable agriculture. His work gained international recognition, inspiring farmers, ecologists, and philosophers worldwide.

What is the One-Straw Revolution?

The One-Straw Revolution is not merely a farming manual—it is a philosophical treatise that challenges the fundamental assumptions of modern agriculture and society. Published in 1975, the book encapsulates Fukuoka’s insights gained over decades of experimentation and observation on his family farm.

The title itself is symbolic. The “one straw” refers to the humble act of returning straw to the fields after harvest, a seemingly insignificant gesture that embodies the cyclical, interconnected nature of life. For Fukuoka, this act represented a profound truth: nothing in nature is wasted, and every element plays a role in sustaining the whole.

In the book, Fukuoka recounts his journey from disillusionment with scientific farming to the development of a system that respects the inherent wisdom of natural ecosystems. He critiques the “industrialization” of agriculture, arguing that reliance on technology, chemicals, and monocultures disrupts the delicate balance of nature. Instead, he advocates for a farming approach that minimizes human intervention and lets nature do most of the work.

The book’s appeal lies in its holistic perspective. It addresses not only farming techniques but also broader themes such as food security, environmental sustainability, and the spiritual fulfillment that comes from living in harmony with nature. Fukuoka’s ideas resonated deeply with those disillusioned by the environmental degradation and social alienation caused by industrialized agriculture.

The Philosophy of Natural Farming

Fukuoka’s natural farming philosophy is encapsulated in his well-known concept of “Do-Nothing” farming. However, this term can be misleading if not fully understood. It does not suggest neglect or laziness; rather, it advocates for minimal human interference and a reliance on nature’s wisdom.

- Harmony with Nature: Fukuoka believed that the best farming practices mimic the natural systems around us. Rather than trying to control and dominate nature, his approach encourages farmers to work in alignment with nature’s rhythms and cycles. This philosophy suggests that by understanding nature’s processes, humans can create conditions where agriculture becomes part of a larger, self-regulating ecosystem.

- Self-Sufficiency: One of the core aspects of Fukuoka’s philosophy is the idea of self-sufficiency. He argued that nature provides everything that crops need to grow, from water to nutrients, if we allow the land to express its natural potential. This extends to his method of farming without external inputs like chemicals, fertilizers, or machinery.

- Simplicity: Fukuoka’s approach is built on the principle of simplicity. He believed that the complexity of modern farming methods, with their machinery, chemicals, and labor-intensive practices, creates unnecessary complications. For him, simplicity in farming leads to better health, sustainability, and food security.

Core Principles of The One-Straw Revolution

The Four Principles of Natural Farming

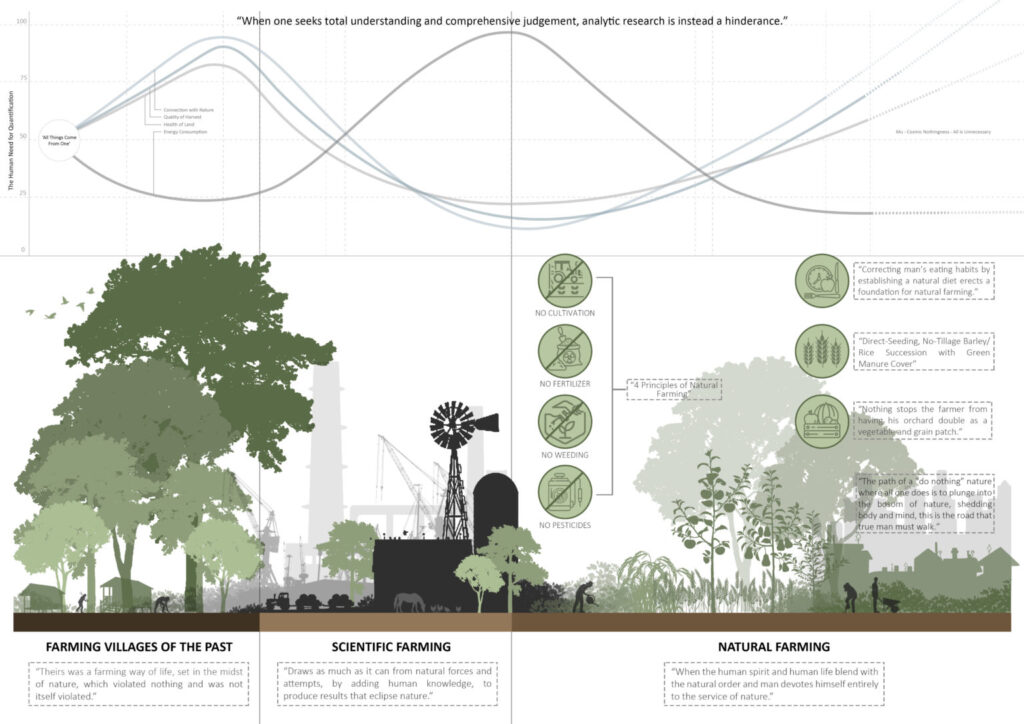

At the heart of the One-Straw Revolution is Fukuoka’s philosophy of natural farming. This approach is guided by a deep respect for nature’s processes and an understanding that human interference often causes more harm than good. Fukuoka distilled his philosophy into four core principles:

1. No Cultivation

Traditional farming often begins with tilling the soil to prepare it for planting. However, Fukuoka observed that tilling disrupts the natural structure of the soil, destroying beneficial microorganisms and causing erosion. He proposed leaving the soil undisturbed, allowing natural processes to maintain its fertility.

- Rationale: Undisturbed soil is rich in organic matter, microbial life, and nutrients, creating a self-sustaining environment for crops.

- Implementation: In Fukuoka’s rice fields, seeds were sown directly without plowing or tilling. The existing soil ecosystem supported the seeds, reducing labor and external inputs.

2. No Chemical Fertilizers or Compost

Fukuoka believed that the excessive use of chemical fertilizers and even prepared compost disrupts the natural nutrient cycles of the soil. Instead, he relied on cover crops like clover, which fix nitrogen in the soil, and the decomposition of organic matter, such as straw, to enrich the land.

- Example: Clover was grown alongside rice and barley to act as green manure, nourishing the soil without human-made fertilizers.

- Impact: This method enhanced soil fertility while preserving the environment from the harmful effects of chemical runoff.

3. No Weeding by Tillage or Herbicides

Weeds, like all plants, have a role to play in the ecosystem. Fukuoka did not see weeds as a nuisance but as beneficial organisms that could support soil health by providing cover, enriching the soil, and preventing erosion.

- Practice: Instead of uprooting weeds with chemicals or tilling, Fukuoka advocated for a more nuanced approach that includes using cover crops, mulching, and crop rotation to manage weed growth naturally.

- Benefits: A diverse array of plants in the field can help prevent soil depletion, maintain pest balances, and protect crops.

4. No Dependence on Chemicals

Chemical pesticides, fungicides, and herbicides not only harm beneficial insects and soil life but also reduce biodiversity, leading to ecological imbalances. Pesticides and synthetic chemicals were avoided entirely in Fukuoka’s system. Instead, he focused on creating a balanced ecosystem where natural predators controlled pests.

- Practice: Fukuoka advocated for planting diverse crops, encouraging predator insects, and introducing habitat areas for beneficial species to promote natural pest control.

- Benefits: Pest populations remain in check through natural predator-prey relationships, reducing the need for chemical intervention.

Philosophical Underpinnings

Beyond these practical principles, Fukuoka’s philosophy was deeply spiritual. He viewed nature as a self-regulating system that humans should respect rather than dominate. He argued that intellectual attempts to “improve” nature often lead to unintended consequences.

His approach contrasts sharply with industrial agriculture, which prioritizes efficiency and profit over ecological balance. Fukuoka saw farming as a way to reconnect with nature, emphasizing simplicity, humility, and harmony.

The Concept of “Do-Nothing” Farming

Fukuoka’s “Do-Nothing” farming goes beyond physical labor—it’s a mindset that reflects a profound respect for the land’s natural processes. The “doing less” concept involves:

- Minimal Intervention: The focus is on observing and understanding nature, rather than manipulating it to fit human desires.

- Learning from Nature: Fukuoka emphasized that farming should be about understanding nature’s methods, not dominating it. The “Do-Nothing” approach stresses patience and observation, trusting that nature will guide the way.

- Clarity of Purpose: Doing nothing is not synonymous with neglect; it’s a deliberate choice to allow nature to take its course and self-regulate.

Practical Applications of Natural Farming

Masanobu Fukuoka’s natural farming system was not only revolutionary in its philosophy but also in its practical implementation. His methods emphasized working with nature rather than attempting to control or dominate it. This approach required an intimate understanding of natural ecosystems and a commitment to simplicity.

Key Techniques in Natural Farming

1. Clay Seed Balls

One of Fukuoka’s most innovative contributions was the use of clay seed balls, a technique that protected seeds from birds, pests, and environmental conditions.

- How They Work: Seeds are coated in a mixture of clay and compost and then dried into small pellets. The clay protects the seeds, while the compost provides nutrients once germination begins.

- Advantages: This method allows for broadcasting seeds directly into fields without tilling or preparing the soil, reducing labor and ensuring better germination rates.

- Applications Worldwide: Clay seed balls have been adopted in reforestation projects and by farmers seeking low-cost sowing methods in degraded lands.

2. Seasonal Crop Rotations

Fukuoka’s natural farming relied on integrating crops into a cyclical, self-sustaining system.

- The Cycle:

- In spring, rice was sown directly into fields already growing rye or barley.

- The rye or barley was harvested in May, and the straw was spread back onto the field to suppress weeds and enrich the soil.

- In autumn, winter rye or barley was sown among the ripening rice plants, continuing the cycle.

- Benefits: This rotation system maintained soil fertility, controlled weeds naturally, and reduced the need for artificial fertilizers.

3. Mulching with Straw

Straw from previous harvests played a central role in Fukuoka’s method.

- Purpose: Mulching suppresses weed growth, retains soil moisture, and provides organic matter as it decomposes.

- Philosophical Symbolism: The act of returning straw to the fields embodied the cyclical nature of life and the interconnectedness of all living things.

4. Orchard and Vegetable Farming

Fukuoka extended his principles to orchards and vegetable farming:

- Orchards: Trees were planted alongside grasses and clover, creating a mini-ecosystem that required minimal human intervention.

- Vegetables: Rather than planting in neat rows, vegetables were grown like wild plants, scattered among grasses or even on hillsides.

- Outcome: This method minimized pests and diseases while producing nutrient-dense, flavorful crops.

5. Limited Irrigation

Unlike traditional rice farming, which relies on standing water, Fukuoka’s method minimized irrigation.

- Implementation: Fields were flooded briefly during the monsoon season to suppress weeds, but rice was otherwise grown with natural rainfall or minimal irrigation.

- Impact: This approach conserved water, making it suitable for regions facing water scarcity.

Fukuoka’s Critique of Modern Agriculture

Masanobu Fukuoka was a staunch critic of the industrial agricultural model that emerged post-World War II. His critique was not merely technical but deeply philosophical, addressing the economic, environmental, and social dimensions of modern farming.

1. Over-Reliance on Technology and Chemicals

Fukuoka observed that modern agriculture depended heavily on machinery, synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides.

- Environmental Consequences:

- Soil degradation from excessive tilling.

- Loss of biodiversity due to monoculture farming.

- Water pollution from chemical runoff.

- Health Impacts: Fukuoka highlighted the dangers of chemical residues in food, which compromise human health.

2. Economic Exploitation

Fukuoka argued that modern agriculture was driven more by economic and political interests than by the needs of farmers or the environment.

- Corporate Influence: Chemical companies, supported by government policies, promoted dependence on synthetic inputs, increasing costs for farmers.

- Farmer Marginalization: Traditional farmers were forced to abandon their methods in favor of expensive, industrialized practices, leaving many in debt or out of business.

3. Loss of Harmony with Nature

Fukuoka believed that the industrial approach to agriculture was fundamentally flawed because it treated nature as a machine to be manipulated rather than a system to be respected.

- Philosophical Insight: He emphasized that nature is inherently balanced and fertile. Human attempts to “improve” it often disrupt this balance, leading to long-term harm.

- Example: The use of chemical fertilizers may boost yields temporarily but depletes soil health over time, creating a cycle of dependency.

4. Critique of the “Efficiency” Paradigm

Modern agriculture prioritizes speed and efficiency, often at the cost of sustainability and quality.

- Fukuoka’s Counterpoint: He demonstrated that natural farming could produce yields comparable to conventional methods without harming the environment.

- Key Message: True efficiency lies in working with nature’s rhythms, not against them.

The Role of Food in Fukuoka’s Philosophy

For Fukuoka, farming and food were inseparable. He believed that how we grow, prepare, and consume food reflects our relationship with nature and our values as a society.

1. The Natural Diet

Fukuoka advocated for a “natural diet,” which emphasized local, seasonal, and minimally processed foods.

- Staples: He promoted the consumption of grains like brown rice and barley, which are well-suited to the Japanese climate.

- Simplicity: Cooking methods were kept simple, often involving just salt as a seasoning, to preserve the natural flavors of food.

2. Connection to the Environment

Fukuoka argued that eating should tie individuals to their environment and community.

- Seasonality: By eating what is available locally and seasonally, people align their diets with the natural cycles of their region.

- Spiritual Benefits: He believed that this connection fosters a sense of unity with nature and contributes to emotional and spiritual well-being.

3. Critique of Modern Diets

Fukuoka was critical of modern eating habits, which he saw as disconnected from nature.

- Imported Foods: He lamented the replacement of traditional crops like barley with imported wheat, which disrupted local food systems.

- Over-Processed Foods: He argued that the pursuit of convenience and novelty in diets leads to poor health and estrangement from nature.

- Materialism in Food: Fukuoka disapproved of viewing food merely as a material commodity, emphasizing that it also nourishes the spirit.

4. Food as a Reflection of Farming Practices

Fukuoka believed that the way food is grown directly impacts its quality and the health of those who consume it.

- Unity of Farming and Eating: He described farming and food preparation as “the front and back of one body,” inseparable and interdependent.

- Natural Food Systems: His vision of food production was deeply rooted in local self-sufficiency, rejecting globalized, industrial food chains.

Challenges and Criticisms

Masanobu Fukuoka’s natural farming method, while revolutionary and inspiring, faced several challenges and criticisms. These arose not only from the practical implementation of his ideas but also from the broader agricultural community’s resistance to change.

1. Labor-Intensive Nature

One of the most significant challenges of Fukuoka’s method is its reliance on manual labor.

- High Physical Effort: Techniques such as hand-harvesting, scattering straw, and manually making clay seed balls require substantial time and effort.

- Modern Farming Contrast: In an era dominated by mechanization, many farmers found these practices impractical for large-scale farming operations.

- Labor Costs: The cost and availability of skilled agricultural workers have made manual labor-intensive methods difficult to adopt, particularly in countries with declining rural populations.

2. Weed and Pest Management

Fukuoka’s principle of “no weeding by tillage or herbicides” presented significant challenges for farmers accustomed to chemical weed and pest control.

- Weed Proliferation: Without tillage or chemical interventions, managing weeds in larger farms proved difficult for many adopters of his methods.

- Natural Pest Control Limitations: While biodiversity and ecological balance help in pest management, they cannot entirely eliminate pest outbreaks, especially in monoculture-prone regions.

3. Limited Scalability

Natural farming, as developed by Fukuoka, is most effective on smaller plots where close monitoring and labor-intensive practices can be sustained.

- Small-Scale Suitability: While it thrived on Fukuoka’s modest farm in Shikoku, scaling the system to large farms or industrialized agricultural setups has been problematic.

- Infrastructure Challenges: Adapting Fukuoka’s methods for regions with vastly different climates, soil types, or agricultural needs also requires significant customization.

4. Resistance from Conventional Agriculture

Fukuoka’s rejection of chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and tillage clashed with the principles of industrial agriculture.

- Economic and Political Pushback: His critiques of agribusinesses and their influence on farming policies led to resistance from companies promoting industrial inputs.

- Farmer Skepticism: Farmers already invested in conventional methods were hesitant to abandon proven practices for an untested system, particularly when initial results varied.

5. Philosophical Misunderstandings

Fukuoka’s philosophical emphasis on simplicity and harmony with nature was sometimes misinterpreted as impractical idealism.

- Complex Concepts: His discussions of “non-discriminating understanding” and spiritual unity with nature were challenging for those focused solely on the technical aspects of farming.

- Perceived Rigidity: Critics argued that his approach was too rigid to accommodate regional variations or the economic realities of farming.

Legacy of Masanobu Fukuoka

Despite the challenges, Masanobu Fukuoka’s work has left an enduring legacy that continues to influence agriculture, environmentalism, and sustainable living.

1. Inspiration for Sustainable Agriculture

Fukuoka’s principles have inspired global movements advocating for ecological balance and sustainability.

- Permaculture Movement: His methods significantly influenced permaculture, which similarly emphasizes working with nature and creating self-sustaining ecosystems.

- Regenerative Agriculture: Many regenerative farming techniques echo Fukuoka’s emphasis on soil health, biodiversity, and minimal intervention.

2. Contributions to Reforestation and Desertification Mitigation

In his later years, Fukuoka expanded his focus to global environmental challenges.

- Reforestation Projects: He worked on reforestation initiatives in arid regions, using his clay seed ball technique to rehabilitate degraded lands.

- Desertification Control: Fukuoka’s methods were applied in Africa, India, and other regions to combat desertification and restore ecological balance.

3. Recognition and Influence

Fukuoka received numerous accolades for his contributions to sustainable farming and environmental conservation.

- Awards: He was honored with the Ramon Magsaysay Award for Public Service in 1988, often referred to as Asia’s Nobel Prize.

- Global Reach: His ideas were popularized in the West through translations of The One-Straw Revolution by Larry Korn, spreading his influence to farming communities worldwide.

4. Educational and Philosophical Impact

Fukuoka’s work transcended farming, inspiring a broader understanding of humanity’s relationship with nature.

- Educational Outreach: His farm in Shikoku became a hub for students, environmentalists, and farmers eager to learn his methods.

- Spiritual Philosophy: Fukuoka’s integration of spiritual and ecological principles continues to inspire individuals seeking a more meaningful and harmonious way of life.

Key Lessons from the One-Straw Revolution

A. Shifting from High-Input to Low-Input Farming

One of the core lessons from The One-Straw Revolution is the importance of shifting away from high-input, industrial farming systems that rely on synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, and large-scale machinery. Fukuoka’s low-input methods emphasize sustainability, long-term soil health, and minimal disruption to natural ecosystems.

- Efficiency in Use of Resources:

- How to Implement: Rather than focusing on high yields, emphasize producing nutrient-dense, flavorful food that contributes to human health and ecosystem health.

- Example: Grow a variety of vegetables, fruits, and herbs with an emphasis on taste, nutritional value, and biodiversity rather than prioritizing volume.

- Long-Term Sustainability:

- How to Implement: Focus on utilizing local resources like compost, organic matter, and natural pest control rather than relying on imported synthetic fertilizers or pesticides.

- Example: Use locally sourced compost instead of chemical fertilizers, and employ integrated pest management strategies instead of chemical pesticides.

B. Redefining Success in Agriculture and Food Production

Fukuoka’s ideas challenge the conventional view of success in agriculture, which typically focuses on maximizing yield. He advocates for a more holistic definition of success, one that considers the health of the soil, the sustainability of farming practices, and the quality of food produced.

- Quality Over Quantity:

- How to Implement: Rather than focusing on high yields, emphasize producing nutrient-dense, flavorful food that contributes to human health and ecosystem health.

- Example: Grow a variety of vegetables, fruits, and herbs with an emphasis on taste, nutritional value, and biodiversity rather than prioritizing volume.

- Biodiversity as a Measure of Success:

- How to Implement: Assess the health of your farm by the biodiversity it supports rather than just the amount of crops harvested.

- Example: A thriving farm should be home to a variety of plants, insects, birds, and other wildlife, creating a vibrant ecosystem that goes beyond simple crop production.

C. Embracing Patience, Simplicity, and Respect for Nature

Fukuoka’s philosophy teaches that true farming success is about patience, simplicity, and working in harmony with nature rather than forcing it into predetermined systems. This mindset can also extend beyond farming into broader life practices.

- Patience in Nature’s Cycles:

- How to Implement: Trust the natural rhythms of the land and allow the ecosystem to heal and regenerate at its own pace. Understand that the best results come with time and observation.

- Example: Allow plants to grow naturally, without rushing or forcing them into specific shapes or sizes, understanding that growth takes time and cycles.

- Simplicity in Approach:

- How to Implement: Simplify your approach to farming or gardening by eliminating unnecessary tools, chemicals, and techniques that complicate the process.

Example: Use fewer tools, fewer inputs, and rely more on natural processes like mulching, composting, and companion planting.

Conclusion

Masanobu Fukuoka’s The One-Straw Revolution offers more than just a guide to farming; it provides a profound philosophical shift toward a more balanced and sustainable way of living with the land. His principles of minimal interference with nature, the rejection of synthetic chemicals, and the embrace of biodiversity continue to resonate in the fields of sustainable agriculture and permaculture. By advocating for a farming system that respects natural processes, Fukuoka’s work challenges modern agriculture’s focus on high yields and synthetic inputs, urging us to reconsider what true success in farming means.

The impact of The One-Straw Revolution on contemporary farming practices is undeniable. From organic farming to regenerative agriculture, Fukuoka’s influence can be seen in movements that aim to create healthier ecosystems and more resilient food systems. While his approach may not be practical for every farming situation, the core lessons from his work—patience, simplicity, and respect for nature—are universally applicable.

As Fukuoka himself said:

“The ultimate goal of farming is not the growing of crops, but the cultivation and perfection of human beings.”

Let this message guide us as we strive for a more sustainable and harmonious future. The lessons of The One-Straw Revolution are not just for farmers—they are for anyone seeking to live in balance with the natural world. By incorporating his principles into both small-scale home gardens and larger farming systems, we can foster a more harmonious relationship with the earth. The One-Straw Revolution provides not only practical insights but also a profound philosophy that invites us to rethink our approach to food production and our connection to the natural world.