Table of Contents

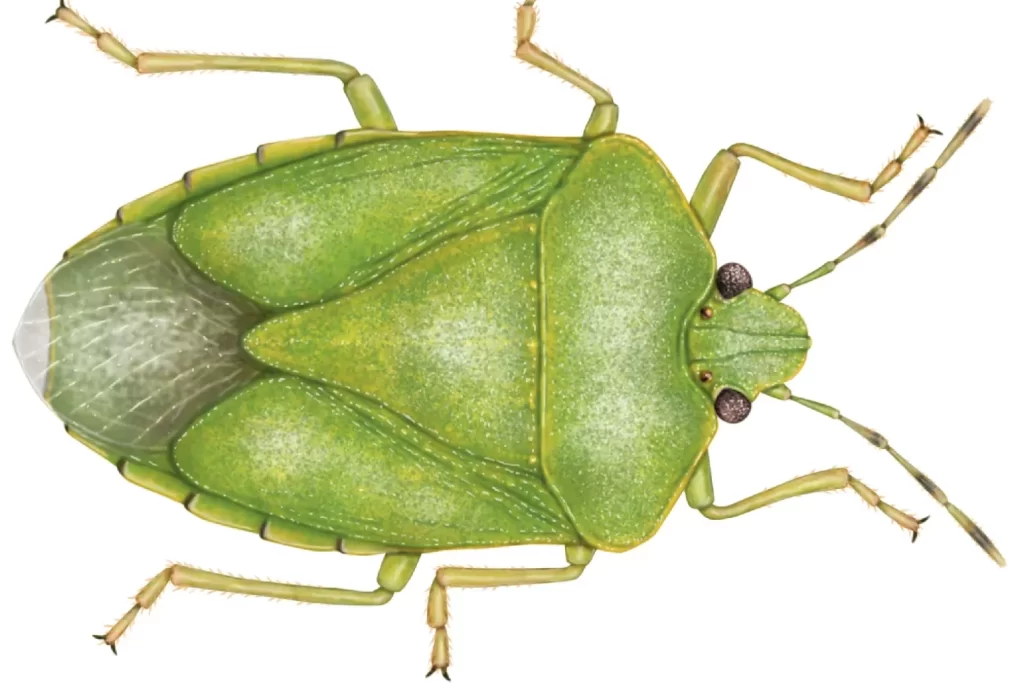

The Southern Green Stink Bug (Nezara viridula) is a formidable agricultural pest that has captured the attention of growers and gardeners across the United States. Recognized by its distinctive shield-shaped body and notorious odor, this insect wreaks havoc on a wide array of crops by feeding on vital plant tissues and paving the way for secondary infections. From the greenhouse to open fields, its polyphagous feeding habits can lead to significant economic losses, particularly in high-value crops such as sweet peppers and tomatoes. This article offers an in-depth exploration of the Southern Green Stink Bug’s biology, the damage it causes, and the integrated prevention and damage control strategies necessary to manage its impact effectively.

Understanding the Southern Green Stink Bug

The Southern Green Stink Bug is a member of the Pentatomidae family and can be recognized by its:

- Appearance:

- A large, shield-shaped body that typically measures about 13 mm in length.

- Dull green coloration in warmer weather that may shift to a brownish hue in cooler conditions.

- Markings such as pale spots on the pronotum and alternating dark and light segments on the antennae.

- Life Cycle:

- Egg Stage: Females lay clusters of 30 to 130 eggs on the underside of leaves and sometimes on fruits. Initially pale yellow, these eggs gradually turn orange before hatching.

- Nymphal Stages: The insect undergoes five instar stages. Early nymphs are reddish with transparent legs and antennae, while later stages adopt a greener color until the final stage, when wing buds emerge.

- Adult Stage: The fully mature Southern Green Stink Bug is equipped with piercing-sucking mouthparts used to extract plant fluids and a defense mechanism that discharges a foul-smelling chemical when disturbed.

- Feeding Behavior and Host Range:

- Fruits and Vegetables: Commonly attacking peppers, tomatoes, and stone fruits, causing necrotic spots and tissue damage.

- Greenhouse Crops: Particularly affecting sweet peppers and other high-value produce, where damage can lead to retarded growth and fruit drop.

- Fiber and Grain Crops: Although primarily problematic in horticultural settings, its feeding habit can sometimes extend to temperate field crops.

- By penetrating the plant tissues with its specialized mouthparts, the bug not only disrupts nutrient flow but also potentially creates entry points for secondary pathogens.

Crops Are Commonly Affected

- Bean

- Bitter Gourd

- Brinjal

- Guava

- Millet

- Okra

- Capsicum & Chilli

- Pigeon Pea & Red Gram

- Potato

- Rice

- Soybean

- Tomato

What caused it?

The damage is caused by a bug called Nezara viridula, which is found all over the world, especially in tropical and subtropical regions. They are called “stink bugs” because they release a strong odour when they feel threatened. The bugs feed by piercing the crop with their thin piercing mouth parts (stylets). The actual feeding puncture is not immediately visible. Both adult and juvenile stages of the bug feed on plants.

They prefer to feed on the delicate parts of the plant (growing shoot, fruit, flower). When it hatches, the juvenile stage of the bug stays close to the eggs. The adults can fly and move around a lot. They are usually green and thus hard to recognize in plants. The colour of the bug changes as it grows, becoming greener with each stage. Usually, they move to higher parts of the plants early in the morning.[1]

Damage Symptoms and Agricultural Impact

The Southern Green Stink Bug inflicts significant damage by directly feeding on plant tissues. Its specialized piercing-sucking mouthparts puncture the epidermis of fruits, leaves, and shoots, yielding several immediate and noticeable symptoms:

- Feeding Punctures and Necrotic Spots:

When the bug pierces fruit surfaces, it leaves behind small pinprick marks that soon enlarge into hard, brownish or black spots. This localized necrosis results from the toxic saliva injected during feeding, which disrupts cell function and tissue integrity. - Deformation of Fruits and Vegetables:

Repeated feeding can cause “catfacing,” a distortion where fruits develop rough, irregular edges or misshapen surfaces. Such deformations may render produce unmarketable, particularly for high-value crops like tomatoes, peppers, and stone fruits. - Damage to Growing Shoots and Leaves:

In addition to fruits, the stink bug targets tender shoots and foliage. The cumulative effect of multiple feeding sites on a single shoot may result in withering, stunted growth, and in extreme cases, the complete dieback of localized plant sections.

One of the critical consequences of the initial feeding damage is the creation of wounds that serve as entry portals for secondary pathogens:

- Fungal and Bacterial Infections:

The punctures and tissue damage not only remove essential sap but also compromise the plant’s natural defense mechanisms. Opportunistic pathogens, including fungi and bacteria, can colonize these open wounds. This secondary infection may accelerate fruit decay and further degrade the quality of produce. - Increased Susceptibility to Post-Harvest Losses:

The damage inflicted during growth can carry over to the post-harvest phase. For example, breaches in the fruit surface may lead to quicker spoilage or microbial growth during storage and transportation, ultimately reducing shelf life and market value.

Prevention Strategies for the Southern Green Stink Bug

Effective prevention of Southern Green Stink Bugs relies on proactive cultural practices, physical barriers, and an integrated pest management (IPM) approach. By addressing the pest’s biology and ecological habits, you can reduce infestations before they become economically damaging.

- Crop Rotation and Diversification:

Regular crop rotation can break the life cycle of the stink bug by depriving it of a continuous host. Changing the type of crop from one season to the next not only disrupts pest reproduction but also reduces the buildup of alternative host plants that might harbor eggs or nymphs. Diversified cropping can complicate the insect’s search for preferred host species. - Weed and Alternative Host Plant Management:

Weeds and volunteer plants often serve as reservoirs for stink bugs, especially around field edges and near greenhouses. Implementing strict weed control both within and around cultivated areas minimizes alternate hosts that facilitate pest buildup. Removing or managing ground cover and maintaining clean borders can significantly lower stink bug populations. - Sanitation and Debris Removal:

Crop residues and plant debris can provide overwintering sites for stink bugs. Regular field sanitation, including the removal or deep tilling of plant residues after harvest, helps eliminate sheltered locations where the insects might survive adverse weather conditions. This practice is particularly beneficial in preventing early-season infestations. - Greenhouse Exclusion Methods:

Installing fine-mesh netting on greenhouse vents, windows, and other openings acts as a first line of defense. In addition to screening, ensuring that all potential entry points—such as gaps in doors and window frames—are sealed with caulk or weather stripping further prevents the movement of stink bugs into the controlled environment. - Barriers in Field Settings:

For open-field crops, erecting physical barriers can be a valuable strategy. Research has shown that using plastic sheets or tall, dense trap crops along field borders can prevent stink bugs from migrating from adjacent areas (such as unmanaged vegetation or alternate host fields) into the primary crop. For instance, a plastic barrier that matches or exceeds the height of the crop can minimize cross-contamination.

Important Tips:

- Remove leaf litter.

- Control the weed growth in your field.

- Plant crops earlier and with larger row width.

- Plant early maturing trap crops, like leguminous and cruciferous plants as these crops attract the bug.

- Plough the trap crop under before the southern green stink bugs become adults and move to the main crop.

Organic Controls For Southern Green Stink Bug

Diatomaceous Earth (DE)

- Mode of Action: Diatomaceous earth is a fine powder composed of fossilized algae. Its abrasive particles damage the insect’s exoskeleton, leading to dehydration and death.

- Application Guidelines: Evenly dust DE around the base of plants and along potential pest entry points. Because DE works best when dry, reapplication after rain or heavy dew is essential. Use food-grade formulations to ensure safety for organic production and non-target organisms.

Botanical Insecticides

- Examples: Products based on pyrethrum (naturally extracted from chrysanthemum flowers) provide rapid knockdown of pests. However, due to their broad-spectrum activity, they should be used cautiously to avoid impacting beneficial species.

- Application Guidelines: Apply these botanicals as spot treatments during peak infestation periods. They are best used in conjunction with other organic methods, ensuring that natural predators are preserved.

The egg parasitoid Trissolcus basalis and the tachinid flies Tachinus pennipes and Trichopoda pilipes have been used successfully to control this pest.

Chemical Controls For Southern Green Stink Bug

In situations where organic measures do not sufficiently suppress the pest population or for growers operating within conventional systems, selective chemical insecticides can serve as an important component of integrated management.

Insecticidal applications are usually not required/necessary; however, sprays may be needed if stink bug populations are high. This pest can be chemically controlled by the use of carbamates and organophosphate compounds. However, since most of these compounds do not last very long on the treated plant, the crop is at risk of being infested again from nearby areas. The effectiveness of insecticidal control can be improved by taking advantage of the times when the pest is active and not hidden within the foliage. Therefore, the insecticides can come into direct contact with them. The stink bug is observed to feed during early morning and late afternoon.

- Pyrethroids (e.g., Lambda-Cyhalothrin): These synthetic chemicals affect the insect’s nervous system, leading to rapid knockdown of active stages.

- Neonicotinoids (e.g., Imidacloprid): Acting as systemic insecticides, neonicotinoids interfere with neural receptors in the central nervous system. They can be applied as soil drenches or foliar sprays. However, regulatory restrictions and concerns regarding non-target impacts—particularly on pollinators—necessitate careful evaluation before use.

Regional Considerations

Subtropical Regions: In the warmer climates of the southern states, multiple generations of the bug can occur. Increased vigilance during the growing season, along with biweekly monitoring, is recommended.

Temperate Zones: In cooler northern states, the pest is more likely to be a greenhouse problem or impact localized field crops. Seasonal sanitation and protective netting become crucial during peak periods.

Conclusion

The Southern Green Stink Bug remains one of the most challenging pests in American agriculture due to its diverse host range and adaptive life cycle. Through a comprehensive management plan—one that emphasizes early detection, integrated prevention, and judicious use of both organic and chemical controls—growers and gardeners can significantly reduce its impact. Stay informed through local extension services and continually update your practices to safeguard crops and maintain healthy growing environments.

If you have any experiences, questions, or additional tips on managing the Southern Green Stink Bug, feel free to leave a comment below or reach out to your local agricultural extension office for further guidance.